- Home

- Fiorella De Maria

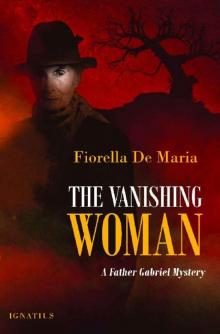

The Vanishing Woman Page 10

The Vanishing Woman Read online

Page 10

9

Gabriel knew now where he had to go next. Douglas had confirmed the niggling suspicion that had kept him awake at night, and there was only one person he could think of who could tell him what he needed to hear: Abbot Ambrose, the fount of all knowledge. Gabriel’s only difficulty was that the abbey was too far away to walk to, and a bus would take hours, winding its way through endless villages between here and his destination. But Dr Whitehead had been foolish enough to offer to help, and in a car he could be there in under half an hour. The doctor would not even have to stay if he did not want to, though Gabriel was sure he would be given a welcome and a cup of tea if he wished. He planned to ask the abbot if Brother Gerard could drive him back when he had finished.

It was not homesickness, Gabriel told himself, as he rushed back to the presbytery to get through his morning chores as quickly as humanly possible; not homesickness as such, but a tiny part of him felt that he was returning to the abbey for reassurance, much as a child might run home to his parents for consolation after a difficult day at school. It was not the first time in his life that he had had this powerful sense that he was walking very slowly in the right direction, albeit in the dark and with every passerby screaming at him to turn around. All the same, the events of the past few days had made him feel lonely. He missed the opportunity to share ideas with sympathetic friends, even friends who might finish the conversation by telling him he was going barking mad.

What with one thing and another, it was half past eleven before Gabriel had some time to himself again, and he made a mad dash to leave rather than face the horror of lunchtime at the presbytery and one of Dorothy’s delightful offerings. Fr Foley’s itinerant housekeeper had never been the most talented of cooks, Gabriel suspected, but the limitations of rationing had shrunk her repertoire to dishes almost exclusively involving corned beef, cabbage, potato and swede, a root vegetable for which he had developed a particular loathing. That said, he thought it would be bad form to turn up at the Whiteheads’ at the moment Mrs Whitehead was serving lunch because she would undoubtedly want to set a place at the table for him and the food she had prepared would have to stretch to satisfy another adult appetite. He could tell her he was expected to eat at the abbey; honour and etiquette would be satisfied.

Gabriel was still some distance from the doctor’s house when he saw a figure up ahead, only just distinguishable in the poor light as a woman in what appeared to be a long coat and a sharp winter hat with little in the way of a brim. She was walking very quickly, virtually running, and Gabriel eventually gave up trying to catch up with her and called out: “Pamela?”

The figure stopped in her tracks and turned to face him. He had been right. It was Pamela Milton, out of breath and more flustered than he would ever have expected to see her. “Father?”

Gabriel closed the gap between them as quickly as he could. “I dare say I’m easy to see from far away,” he said lightly.

“Yes,” she answered with a half smile, “You look like Count Dracula. I suppose you’ve heard the news then?”

Gabriel felt his heart sink; of course he hadn’t. He had been stuck in the parish office all morning, but he knew what must have happened, or Pamela would not be running to the scene. “Agnes?”

“Yes, I thought that must be the reason we were heading in the same direction. I’m trying to reach the doctor’s house before they take her away.”

Gabriel touched her arm in what had been intended as a comforting gesture, but Pamela turned away and continued walking, allowing him the privilege of trotting along beside her. “You know, it may be for the best, and it won’t be for very long. Douglas said the place is very nice.”

Pamela stopped again, looking at him as though he were a blithering idiot. “What are you talking about, man? I was at the bookshop with my daughter when someone came in and said that the police were going to arrest Agnes. Apparently, that clot of a PC Plod has decided that Agnes is an accessory to murder. She is supposed to have made up the story of seeing her mother through the window to detract attention from what was really going on. You know, causing the police to keep the search local, diversion tactics, blah blah blah, the usual nonsense. The idea being that the killer, whoever it is supposed to have been, could dump the body and have plenty of time to cover his tracks. It’s like something out of an Agatha Christie.”

They continued walking. “But I thought Enid Jennings had been seen leaving the railway station? If that’s the case, the police must be able to ascertain that she came back to the town even if she didn’t return home. If so, it suggests—”

“Yes, yes, yes, Father, I catch the drift. The problem is, as George—Mr Smithson—was kind enough to point out earlier, it will be almost as difficult to prove that Mrs Jennings arrived at the railway station as it will be to prove that Agnes saw her spectre through the window. There are plenty of old ladies in big hats getting on and off trains. They’ll just argue that the stationmaster saw someone else getting off the train. Mrs Jennings was hardly the most sociable old crone in the town; she would not have stooped low enough to talk to anyone. Any good legal counsel would demolish a witness who claimed to have seen her.”

“What a mess” was all Gabriel could think of saying, and he immediately wished he hadn’t bothered. He thought: You are giving this far too much thought, Pamela. What are you playing at?

“That’s the understatement of the decade!” snapped Pamela. “I just wish to goodness she hadn’t been alone. If we’d stayed a little longer or Douglas hadn’t felt the need to push off . . . I thought it a little rude anyway at the time.”

“Well, it was certainly very convenient of Douglas to disappear like that,” mused Gabriel aloud, another comment he immediately regretted.

Pamela went quiet, ostensibly to catch her breath, but as though aware that Gabriel was reading her thoughts, she said quickly, “Fortunately, he went to a public place where people knew him.”

“Indeed. There would have been only about half an hour either side of his arrival at the pub in which his movements were unaccounted for. Forgive me. Why not forget I said that?”

“Consider it forgotten, Father. I don’t suppose Applegate has asked you where you were at four o’clock on that afternoon, has he?”

“Touché. Oh dear.” Gabriel came to a halt like an exhausted marathon runner taking a few pathetic final steps. “This does not look promising at all.”

Inspector Applegate’s car was parked awkwardly in front of the handsome facade of the Whiteheads’ house. Gabriel and Pamela could hear what sounded like a violent argument, and they both rushed to the door, Pamela arriving shortly before Gabriel.

Inspector Applegate and Mrs Gilbert were standing in the hall in the middle of a blazing row. Applegate’s normally dour complexion was flushed with unprofessional anger, whilst Mrs Gilbert wore the look of a woman whose territory has been invaded by the Visigoths. “It’s no good threatening me, Inspector,” she hissed at him, as though the word “inspector” were an expletive. “I had nothing to do with the decision. Mr Jennings thought it would be better for her.”

“Did you drive her to that so-called clinic?” thundered Applegate. “I’ll have you arrested for obstructing the police.”

“Inspector—” Gabriel began, but the interjection sounded no stronger than a whisper in the context of two raised voices.

“Of course I didn’t, you imbecile; I can’t drive!”

“The doctor then?”

“He’s been busy with patients all morning.”

“Inspector, look behind you,” said Gabriel, but the effect was disastrous. Reminded of a pantomime scene, Pamela burst out laughing, causing both Applegate and Mrs Gilbert to turn and look at them. Gabriel looked apologetically at Applegate. “I really would look behind you.”

Standing in the doorway leading to the adjoining surgery stood a thin, white-haired woman and a much taller, younger woman with soft blonde curls; they were evidently mother and daughter. In her arms,

the young woman held a baby who was whining softly and looked as if he had been woken up by the noise. “What do you think you’re doing?” demanded the white-haired woman in a surprisingly strong tone. “How dare you come into my house and interrogate my housekeeper like this for half the town to hear. We could hear you shouting from the waiting room.”

“I’m sorry, Mrs Whitehead,” said Applegate, “but I’ve come here on serious business. I’m afraid I need to arrest Agnes Jennings, and I gather that she’s been spirited away to some loony bin or other.”

“I’m not sure I know what you mean by that term,” answered Mrs Whitehead, stepping determinedly into the centre of the room. Gabriel marvelled at how such a physically unimposing person could so easily take control of the situation. They had all gone quiet, including Applegate, who for the first time looked a little awkward. “Would you care to remove your hat?” she asked, diminishing Applegate even further; he fumbled to remedy the oversight. “Now, for your information, Agnes was not spirited anywhere. I drove her to the clinic myself over an hour ago. If you are going to arrest anyone for getting in your way, I’m afraid you’ll have to arrest me. Then, you can drive over to Greenford’s and arrest Agnes in her sickbed.”

Gabriel glanced from face to face and noticed that the four women were all glaring at Applegate in accusation, a detail not lost on Applegate either. He drew a deep breath, spreading his hands in front of him as though in self-defence. “Now look, Mrs Whitehead, Agnes is not sick, she’s hiding—”

“My husband thinks otherwise,” answered Mrs Whitehead, coldly. “At which medical school did you train, Inspector?”

Applegate flinched with the final undermining remark he was apparently capable of enduring; he turned his back and pushed past Gabriel and Pamela in his determination to remove himself from the advancing female army. Gabriel nodded in Mrs Whitehead’s direction before following Applegate outside.

“Inspector?” he called, but Applegate already had his hand on the gate and the constable had got out of the car to come and speak with him. “Inspector, please wait a moment.”

Applegate turned on him, unleashing the pent-up fury of the past ten minutes. “You knew they were taking her away, didn’t you?” He roared. “Admit it, you were in on the whole plot!”

“I very much doubt it is a plot,” tried Gabriel, “but if you really think she’s an accessory—”

“I don’t know who told you that. I wasn’t about to arrest Agnes for being an accessory to murder; the charge is murder.” Gabriel opened his mouth to respond, but Applegate cut him off. “We all swallowed the idea that she was in that house all along, didn’t we? But who can vouch for her after Dr Milton and the others left? She has no alibi at all from three o’clock that afternoon until the following day. Oh, don’t pretend to be shocked!”

“Her brother can vouch that he found her in a distressed state near the house that evening. I know there are still some unaccounted-for hours, but even so—”

“Laudable for a man to give a false alibi for his own flesh and blood. I suspect we might both do the same. And if you think I believe his story, you must think I believe in Father Christmas. I’d wager she got that blow to the face from her mother trying to defend herself.”

“I’m sure Douglas is an honest man; he’s a man of the law.”

Applegate gave an appalling, sneering laugh. “What sweet naivety, Father! No lawyer has ever lied to the police.”

“Inspector—”

“Look here,” said Applegate with the tone of a man who is closing a conversation once and for all. “I don’t know who it was who said that doctors are the most dangerous men in the state, but they’re not. Lawyers are. They’re clever; they know the workings of the law; they know how to cover their tracks.”

“Inspector, what evidence can you possibly have? Enid Jennings died at Port Shaston. It’s not even clear if she met a violent death at all.”

“What?”

Gabriel instinctively took a step back from Applegate’s piercing gaze. “It looks as though she didn’t drown,” he said lamely. A sudden image came into his mind of one of those propaganda posters depicting two women chatting together over a cup of tea with Adolf Hitler in the background listening in: Careless talk costs lives.

“The information I have been given is that she drowned,” said Applegate emphatically, and there was only the slightest threat in there somewhere. “The results of the postmortem are not yet available.” Gabriel looked away, unwilling to volunteer any further information. “I’ll thank you not to interfere any further,” said Applegate in little more than a whisper. Gabriel suspected that the occupants of the house were watching them from the doorway, and he struggled not to reveal anything through his body language. “I wouldn’t want to have to lock you up as well.”

“On what grounds?”

“I don’t know, Father,” whispered Applegate, looking him coldly in the eye. “Rumours can spread quite quickly in a little place like this, even false ones.”

Gabriel swallowed hard as Applegate opened the gate and walked with the constable to his car. He watched as the car drove away, aware of the queasy feeling creeping through his gut. He took so long to come to himself that he eventually became aware of a hand on his shoulder. “Father, whatever is the matter?” asked Pamela. “What did he say to you?”

Gabriel was conscious of the determined hand of another person taking him by the arm and leading him back into the haven of the Whitehead house. “It’s nothing,” he said, but Mrs Whitehead was immediately fussing, telling Mrs Gilbert to fetch some brandy from the cabinet. He was vaguely aware of the sound of a baby screaming upstairs and realised where the other woman had gone. “I’m quite all right,” he said quietly. He was almost more shocked at his own clumsy handling of the situation than Applegate’s threat.

“You’re nothing of the sort,” said Mrs Whitehead, leading him into the kitchen where he was immediately assailed by the glorious aroma of bread baking. “I hope you don’t think it improper of me to bring you into the kitchen, Father, but it’s the warmest room of the house in winter and your hands are freezing.” He sat in a surprisingly comfortable wooden chair by the stove and watched her opening a large tin. “I’m just glad Agnes is safe for the moment. Evil little brute. And didn’t even have the manners to remove his hat. Did you see the state of his boots?”

Gabriel shrugged miserably. “I’m not sure I did, Mrs Whitehead. Don’t worry about getting cake out for me; it’ll spoil my appetite.”

Mrs Whitehead gave an indulgent smile and handed him a generous slice of fruitcake. “Excuse me if I can’t give you a larger slice,” she explained, “but you know what paraffin can do to the constitution. I have found ways to produce plenty of food, but sugar and butter remain elusive. There now, let me see where Mrs Gilbert has got to with that brandy.”

“Really, I—” Mrs Gilbert was pressing the glass into his hand, and he had no energy to resist her kindness.

“Threatened you, did he?” asked Mrs Whitehead, pulling up a chair and siting down opposite him. She had the kind, cheerful face of a woman who has led a largely contented and sheltered life at the heart of a happy home. She had no pretensions to great beauty but was the sort of person one could warm to effortlessly. “Don’t take any notice, Father. The police don’t know what they’re doing, and one of my husband’s chums has told me that you are good at puzzles.”

“I’m not sure I’m making a very good job of this one,” Gabriel admitted. The cake was more of a treat than the brandy, and he felt himself warming up immediately as he sank his teeth into the soft, crumbly sweetness. “You are very fond of Agnes?” he asked between mouthfuls.

“She’s practically family, Father,” said Mrs Whitehead. “There were times after her poor father died when she virtually lived here. It was difficult at home. For all her reputation as a battleaxe, Enid Jennings—God rest her soul—couldn’t cope at all after her husband’s death. Douglas was old enough to look afte

r himself, for the most part, and then, of course, he was called up as soon as he turned eighteen, but Agnes needed somewhere to turn.”

“It was very good of you.”

“It was nothing,” Mrs Whitehead assured him. “She’s a dear little thing, always was. She and Therese were like sisters for a time.”

Gabriel was finding it awkward to talk and eat tidily at the same time. He endeavoured to keep his hostess talking. “Are they still close?”

Mrs Whitehead’s smile faded. “They drifted apart when they started growing up. It happens with girls, always falling in and out of friendships. They’re on cordial enough terms now that they’re both grown.” She hesitated. “Forgive me, Father, but did you come to the house to see Agnes again?”

“I’m afraid I didn’t,” admitted Gabriel, letting Mrs Whitehead remove his empty plate with only the smallest regret. “Though it’s because I’m trying to help Agnes that I wanted to ask a favour.”

“Of course. What is it?”

Gabriel cringed with the English embarrassment of asking for anything. “I need to go to my abbey. There’s someone there I wish to consult about this matter. It’s just that it’s rather a distance and the buses are dreadful . . .”

“I’ll run you over as soon as I’ve laid out the lunch things,” she said with a smile.

It is strange the way memory can play tricks on a man’s sense of time passing. As they came into view of the abbey, Gabriel could have believed for a moment that he had been away for only a couple of days. It felt so natural to be there, all the more so after he had clambered out of the car and waved Mrs Whitehead goodbye, finding himself alone in a particular spot where he had once walked every day.

That was the strangeness of it. He had imagined walking along the path to the gates with a lump in his throat, feeling his eyes misting over with the joy of returning home, but it felt so normal to be home that no emotion touched him at all. He simply rang the bell, a little regretfully because he realised that he had mistimed his visit. The delay caused by his altercation with Applegate and subsequent chat with Mrs Whitehead had meant that they had left the house much later than he had hoped and lunch would be long over. On the bright side, however, it was a time of recreation now, which might make it a little easier for him to speak with the abbot alone.

The Vanishing Woman

The Vanishing Woman