- Home

- Fiorella De Maria

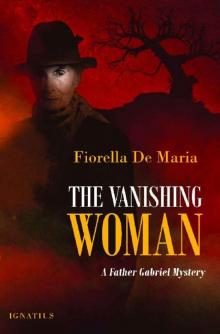

The Vanishing Woman

The Vanishing Woman Read online

The Vanishing Woman

Fiorella De Maria

The Vanishing Woman

A Father Gabriel Mystery

IGNATIUS PRESS SAN FRANCISCO

Cover images:

Photograph of woman © iStockPhoto.com

Photograph of tree by Vincent Chin on Unsplash.com

Cover design by John Herreid

© 2018 Ignatius Press, San Francisco

All rights reserved

ISBN 978-1-62164-223-7 (PB)

ISBN 978-1-68149-792-1 (EB)

Library of Congress Control Number 2017951077

Printed in the United States of America

Contents

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

More from Ignatius Press

1

Gabriel took a deep breath, rather like a swimmer about to plunge into icy water, before he stepped from the warmth of the presbytery into the bitter cold of the courtyard. Even with the protection of a thick black coat, he felt the chill of that early December evening and pulled his hat down firmly over his ears. For once, he was grateful for the long black woollen scarf Mrs Whitehead had knitted for his birthday the previous month and wondered whether he could prevail upon her to knit him a pair of matching gloves for Christmas if he asked her very nicely.

The presbytery sat snugly next to the Church of Saint Patrick, a building ludicrously out of character with the rest of the street, with its large, garish green doors complete with shamrock door handles, but he had become quite fond of the old place in the nearly three months he had ministered there. The priest who had built the church some fifty years before had been an Irish member of the Salesians of Don Bosco and had made no secret of his political allegiances. The bars protecting the street-side windows were an unfortunate reminder of the attack on the church in 1916 at the height of the Easter Rising. A group of angry youths on leave from the Front had smashed the windows and dropped burning rags through them, starting a fire that would have destroyed the building had the sacristan not been present to summon help.

Thank God for gentler times. Gabriel still had some fairly vociferous opponents, but these days they tended to limit themselves to turning their backs on him in the street or sending him poison-pen letters about why he and the Scarlet Whore of Babylon were doomed. Even when the subject matter was intended to hurt, the writers were so English and provincial that the letters would still be written in neat italic hand on fine paper, every word of disgust correctly spelt and grammatically appropriate to the sentence. Some even signed themselves off with “yours sincerely” or even “with kind regards and every good wish”, the polite reflex enduring through the waves of sectarian loathing.

The brisk stroll to the town hall lasted nearly fifteen minutes and took Gabriel much of the way down the long street that cut the town in half. He passed the graveyard with its low stone wall, the line of metal stubs serving as a reminder of the vast metal railings that had been taken away and melted down to build Spitfires years before. Someone had put up a wooden sign to replace the metal one that had also been taken away, with the promising message etched inexpertly: Mors Ianua Vitae.

Gabriel noticed that some well-wisher had left fresh flowers at one of the graves and felt his belief in humanity being restored. The grave belonged to an elderly spinster who had died some years ago. According to old Fr Foley, she had died entirely alone, and only one parish stalwart attended the funeral. Someone, out of the goodness of his heart—perhaps because the old lady’s anniversary was approaching—had chosen to ensure that her grave was not neglected. Gabriel rather hoped that someone would do that little courtesy for him one day, not forgetting to say a little prayer for his suffering soul.

There was a visible social divide between one side of the street and the other. The houses on the left were large, impressive redbrick affairs, all of them with well-kept little gardens to set them back a bit from the road. The dwellings on the side of the road along which Gabriel was walking were smaller terraced cottages built for labourers and artisans. They had no gardens to separate them from passersby like his nosy self, but every pair of windows was daintily concealed by net curtains, and most had window boxes or hanging baskets that would erupt in a riot of colour in the spring.

He crossed a side street that led in the direction of the sprawling army barracks with its rows and rows of Nissen huts and perimeter fences decorated in barbed wire. If an intrepid traveller followed the path several miles farther uphill towards the plain, he would stumble upon the deserted village requisitioned by the Ministry of Defence during the war for use by the army. Some of the villagers attended his parish, having settled reluctantly nearby. They still talked bitterly about the day in 1943 when official-looking gentlemen had convened a meeting in the village schoolroom, giving the inhabitants forty-seven days to clear out. The village was in a position of strategic interest. They were promised homes elsewhere and told that as soon as the war was over they could return and rebuild their community. Gabriel had a feeling that the disgruntled former inhabitants of the village would never be allowed to resettle there; or by the time they were, those houses and shops, the school building and the church would have suffered so dearly from long abandonment and the rigours of many mock street battles as to be uninhabitable.

Gabriel walked down High Street, where the little shops on both sides of the road had their blinds and shutters down and their signs and outside furnishings safely locked away inside. Trade was thriving, surprisingly in these days of “make do and mend.” The town boasted a butcher, two bakeries, a greengrocer, a haberdasher and a corner shop that was not in fact on a corner but that sold everything from comic books to tins of corned beef. There were also a bookshop, more public houses than it was decent to mention and reportedly the finest tea rooms in the county.

Gabriel had a suspicion he was a little late, as there were very few people about as he crossed the road at the central crossroads and made his way up the steps through the grand blue double doors of the town hall. He was right. As soon as he stepped into the anteroom, Gabriel was accosted by Douglas Jennings, who stood awkwardly with his finger held theatrically to his lips to indicate to Gabriel not to speak above a whisper; the doors to the main hall were open, and the talk had already begun.

Douglas was a solicitor in training and looked every bit the part, from the gawkily parted hair held stiffly in place with Brylcreem to the smart if slightly archaic three-piece suit that had evidently been his father’s. It had no doubt been brought out of storage when required, since clothing coupons were still in short supply, and it would be a long time before he could acquire himself a new one. Gabriel could almost smell the mothballs.

“Good evening, Father,” whispered Douglas, indicating the open doors in case Gabriel had failed to work out which way he needed to go. “Pamela asked me to greet any stragglers. There are still a few seats at the back.”

Gabriel nodded in acknowledgement and tiptoed into the hall, pleasantly surprised to see how full it was. There was little in the way of entertainment to be had in the small town, particularly at this time of year, nevertheless people were often reluctant to go out on cold, dark winter evenings when they could just as easily make themselves comfortable with the wireless and a good book. He recognised many faces. Some people were evidently interested in the speaker’s topic, some were there to support an old friend who had returned to the town for a rare visit and some who lived alone (sadly there were plenty of those thes

e days, many of them women) craved the presence of others and the chance of conversation after the talk, when the tea and hopefully some cake were served.

Gabriel settled himself into his seat as best he could and focused his attention on the speaker. Dr Pamela Milton, an academic in her thirties with a minor position at an Oxford college, was giving a talk about Alfred Lord Tennyson and the theme of memory. Gabriel wondered whether the subject would be a little on the lofty side for the likely audience, but he was immediately impressed by how easily Pamela seemed able to engage her listeners. It helped that she was worth looking at for any length of time. She was dressed in slacks, which Gabriel suspected did not go down well with some members of the audience, and she wore her hair short, in a style that was evidently supposed to be quite masculine but merely made her look impish, more a tomboy than a bluestocking aggressively making her way in a man’s world. She wore no makeup or jewellery, but Gabriel doubted that this was carelessness on her part. Every detail of Pamela’s carefully presented image was clearly intended to give the impression of a working woman—professional, no-nonsense—but in spite of her best efforts, she exuded an aura of sensuality Gabriel was not sure he was even supposed to have noticed.

“What does it mean to remember?” She almost purred, giving the audience a knowing smile that seemed to be directed personally to everyone present. “For that matter, what do we mean when we speak of keeping a person’s memory alive? The very title of Tennyson’s famous poem “In Memoriam” immediately provokes such a question. We make it our business to remember the dead; some of us believe we have an obligation to remember and pray for the dead. After a war in which millions have lost their lives, we are perhaps more aware than ever before of the need to remember, the need to keep alive the memories of those we have loved.”

Gabriel sensed the subtle change in atmosphere, as members of the audience began to think about the people they had lost, a change Pamela had effortlessly engineered. “Arthur Hallam was Tennyson’s beloved friend, tragically drowned in the prime of his life, and it was that loss Tennyson sought to understand when he set about writing his famous poem, or I should, of course, say collection of many poems. It is said to have been a favourite of Queen Victoria’s, herself overcome by grief at the loss of her husband, and it is perhaps because it is part of the human condition to love, to mourn and to remember that Tennyson’s words strike a chord across the decades.”

The smile had been quietly replaced by a soulful expression, enhanced by the slight angle at which Pamela held her head. “ ’Tis better to have loved and lost than never to have loved at all,” she recited. “Consider for a moment, privately, the person or persons about whom you would write a poem if you were so inclined. Consider them whenever Arthur Hallam’s name is mentioned or inferred from now on.”

Gabriel felt suddenly very hot. He was not a man who blushed easily at his age, but he felt his cheeks reddening as he struggled to obey her instruction. He saw a face, faces—for who at his age and of his generation had only one loved one to remember?—but he found it impossible to allow their features to snap into focus. For the rest of the talk, Gabriel allowed himself to be distracted by Pamela Milton’s expertly choreographed performance. He concentrated on the tiny details of her voice—the well-rounded vowels and the occasional creep of her West Country accent slipping back through the layers and layers of education; the strange singsong way she had of speaking that could be both commanding and flirtatious at the same time—the well-chosen yet apparently spontaneous quips and turns of phrase, her firm stride as she walked from one side of the platform to the other and occasionally left the platform altogether and stepped into the aisle that parted the audience.

’Tis better to have loved and lost . . . Gabriel was not even a fan of Tennyson, but that was one line he did know—that and Water, water everywhere and not a drop to drink. No, that was the other chap, he corrected himself, the one who smoked strange things but wrote something rather lovely about Our Lady in the same poem. Keats? No, Coleridge, in “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner”.

“We remember . . .” he heard her voice calling to him through his own confusion. “We remember because we too wish to be remembered. To keep a loved one’s memory alive is as much about remembering the value of that person’s life as it is a statement that we all have and deserve a place in the world, even after we have left it.”

Gabriel joined in the applause, watching as George Smithson—the organiser of the event—stepped onto the platform and shook Pamela’s hand enthusiastically. “Well,” he said, when the applause had died down enough for him to speak. “I think we may thank Dr Milton for a most insightful talk about Tennyson. It is such a privilege to have Dr Milton with us again. As many of you know, she is a local and will be staying with her mother for some weeks over Christmas. I gather she has a book to finish.” George gave Pamela an ingratiating smile. “I’m pleased to say we have a number of Dr Milton’s books on sale here this evening and also in my shop—” There was a patter of laughter from the audience at the blatant advertisement. “Yes, in the bookshop, in pride of place. Dr Milton has kindly agreed to sign copies at the shop tomorrow afternoon between two and five o’clock. Now, I know it is getting late and many of you will be in a hurry to get home, but if there are any questions . . .”

There was a nervous silence as everyone in the room waited for someone else to put his hand up first. For a moment it looked as though nobody would pluck up the courage, and Gabriel was just trying to formulate a friendly question to set the ball rolling when an elderly woman stood up to speak. It was Enid Jennings, the former headmistress of the local school and personal nightmare of every inhabitant of the town under the age of forty who had not had the good fortune to be sent away for his education. She was a thin, physically unimposing woman with grey hair scraped away from a craggy face that had frozen into a permanent scowl decades ago. Her habit of constantly narrowing her eyes was quite possibly caused by failing eyesight that she refused to acknowledge, but it had the unfortunate effect of communicating contempt and displeasure before she had even opened her mouth. The change in Pamela was noticeable. She held the older woman’s gaze, her jaw set as though she were clenching her teeth with the effort of having to look at Mrs Jennings at all. Her hands were clasped tightly behind her back.

“I should like to ask a question, if I may,” Mrs Jennings began, in precisely the cold, faintly sneering tone one might have expected of her. “I have here a copy of an article you wrote some time ago for the journal Mentor, in which you dared—”

“Madam, I am not sure you are asking a suitable question for this evening,” George put in quickly, sensing where things were going. “Perhaps if you were to ask Dr Milton privately—”

“Young man,” Mrs Jennings interrupted, waving the offending journal in his direction, “if I wished to discuss this with Miss Milton privately, I should not have failed to do so. Since Miss Milton has been kind enough to talk for over half an hour on a subject about which none of us are interested, I’m sure it is not too much trouble for her to speak for a couple of minutes about a matter of profound importance.” She glanced back at Pamela. “You wrote an intemperate article against what you term ‘the antiquated teaching methods of the older generation’, in which you refer to a number of such methods that feel a trifle familiar to me. Are you aware of the seriousness of defaming an individual in print?”

“You are the one making the accusation, Mrs Jennings,” answered Pamela coldly, but her cheeks were flushed with either anger or embarrassment. “If you had taken the trouble to read the article, you would notice that I mention no individual by name—”

“You are not answering my question, girl,” said Mrs Jennings, in the sort of tone she would have used towards an eleven-year-old miscreant she was interrogating in her study. “I said, are you aware—”

“I am perfectly aware. I stand by every word I—”

“My son is a solicitor, and he has told me—”

<

br /> “Don’t we all know it!” called a rasping male voice from two or three rows in front of where Gabriel was seated. “Enid Jennings, the solicitor’s mother!”

George Smithson had stepped in front of Pamela like a fireman desperately trying to find a way to contain a blaze before it turns into a raging inferno. “Well, I think there are one or two other people who would like to ask Dr Milton a question about the subject of her talk. Perhaps we could—”

“I haven’t finished yet!” barked Mrs Jennings, but someone at the front was standing up unbidden, revealing bodily proportions of the type that tend to bring arguments to an abrupt halt. “Excellent speech!” he called out, clapping enthusiastically. The rest of the gathering took the hint and began applauding with equal enthusiasm. Enid Jennings, who had never faced a classroom mutiny in her entire life, glanced about her in disbelief before fixing her glare on Pamela as though she, not the unnamed rugby player, had led the conspiracy against her. Pamela returned the compliment and glowered back.

“Let me get you a nice cup of tea,” said George to Pamela, as the audience began to disperse and a few enthusiasts edged towards the platform to speak to her. “Don’t waste your time on that old trout if she comes over; you have plenty of friends who want to talk to you.”

Pamela giggled and turned to greet Dr Whitehead, a man who had known her since the stormy night long ago when he had dragged her screaming into the outside world. “Good to see that you are keeping the worthies of the town on their toes,” he said with a warm smile, taking her hand unprompted to help her down from the platform. “Half the town will be wanting to read that article now, I should think. Nothing like the whiff of notoriety.”

“I do hope so.”

Dr Whitehead was a portly man who looked as though seniority had crept up on him all of a sudden one day, turning his hair effortlessly from brown to grey and adding a paunch to an otherwise fit, powerfully built frame. He handed Pamela a copy of one of the books George Smithson had laid out on trestle tables along the wall. “Would you do me the honour?” he asked. “I promised Therese I would bring back a copy. She was so sorry not to be able to come today, but her baby is under the weather and she didn’t want to leave her mother to nurse him all evening.”

The Vanishing Woman

The Vanishing Woman