- Home

- Fiorella De Maria

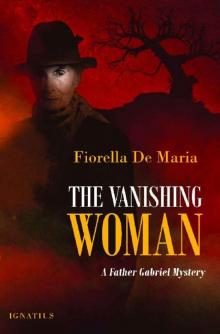

The Vanishing Woman Page 15

The Vanishing Woman Read online

Page 15

Fr Foley blinked in surprise. “I entered the aspirantate at eleven, junior seminary when I was thirteen. Why?”

“Have you ever looked back?”

The old man considered for a moment before saying casually, “Never,” and filling his mouth with food as though to draw attention to the silliness of the question. When Gabriel failed to make any response, he swallowed and said, “Not having any wee doubts now, are we?”

Gabriel shook his head, too dejected to be offended. “Not at all.”

Fr Foley sighed. “I’d forgotten, the best wine was left until last with you, wasn’t it?”

“I’m not sure about that,” said Gabriel softly, “but yes, I did arrive a little late in the day. But by the time I entered seminary, there wasn’t very much to look back to.”

Fr Foley got up and filled Gabriel’s glass for him, patting him on the shoulder as he did so. “You’re run down, my boy, that’s all. Get outside of that food and let me get you something to make you sleep. A good night’s rest—that’s all you need.”

Fr Foley obviously had a point, because Gabriel woke up next morning with the serene feeling of a man who has enjoyed eight hours of drugged, dreamless sleep. The effects of the sedatives—which, contrary to Fr Foley’s promise, had proven to be quite powerful—were to leave Gabriel feeling drowsy and somewhat detached from the rest of the world as he got himself up, wandered over to the church and said Mass. It was rather like looking at the world through a thin glass tube. Everything was as it should be, and he was as he should be but just a little separated from it all.

He knew he had a busy afternoon and could not afford to let Fr Foley down again, so he made his way directly to Pamela Milton’s family home without stopping to break his fast, an omission that made him feel only more lightheaded and separate from everything around him. He wondered whether it would make him more objective, this sense of being outside of things, but by the time he reached the smart neighbourhood of Queen Victoria Road, with its grand redbrick houses surrounded by trees and expansive lawns, Gabriel could feel himself falling back down to earth with a bump.

The Miltons were well-to-do and unashamedly so, the recipients of family money or good fortune in business. Gabriel found, when he reached the family residence, that he had to ring the bell at the front gates to gain entrance, a practice almost unheard of in this trusting little town. Moments later, he looked through the slats of the wooden gates—put there to replace metal railings, he suspected—and saw Scottie bounding towards him like a boisterous Labrador, her face pink with the cold morning air.

“Good morning!” She greeted him warmly, lifting the latch and heaving the gate open. “Come in.”

“That was quick!” answered Gabriel, gratefully, following her into the garden. He spotted a treehouse in the near corner and realised that Scottie must have been playing outside and seen him coming; hence her rapid appearance.

“I was watching the road for spies,” Scottie explained, curling her hands around her eyes to suggest binoculars. “Then I saw you. Oh well, I suppose you could be a spy.” She reached out and took his hand without a second thought, walking with him in the direction of the front door. “I suppose you’ve come to see my mother?”

“Yes, I have.”

Scottie had the easy confidence and trust of a child growing up surrounded by adult company, which had made her charmingly precocious rather than spoilt—Gabriel suspected Pamela would be far too sensible a parent to overindulge a child, even a precious only child with a war-hero father. “Uncle George calls you Sherlock Holmes, but I said that was silly. You don’t have a magnifying glass or one of those hats, though I do believe Sherlock Holmes hadn’t a wife either.”

Gabriel found his companion disarming and could think of little else to say other than, “Well, I suppose I could buy myself a deer-stalker hat.”

Scottie shook her head impatiently. “I’m not sure priests are supposed to wear things like that, are they?”

Scottie’s mother had evidently heard her daughter’s prattling from inside the house and threw open the front door before Gabriel could attempt the social nicety of knocking. Pamela wore a look of affectionate exasperation and immediately put her hands on her hips. “I do hope you haven’t bored Father to death already?” she asked, planting herself firmly between Scottie and the comfort of the inside. “And where do you think you’re going with those muddy boots, young lady?”

Scottie looked sheepishly at her gumboots, which were plastered in mud and dead leaves. “I thought it might be time for elevenses,” she said hopefully.

“You’ve barely finished your breakfast,” answered Pamela, pointing outside. “Go on. Father is here on very secret business, so you had better keep sentry duty until he’s left. We don’t want any nasty eavesdroppers coming in.”

Scottie sighed resignedly. “You’re getting me out of the way,” she said matter-of-factly. “May I have my elevenses in the treehouse today then?”

The two females exchanged knowing looks. Gabriel suspected that their domestic life was full of little moments of negotiation such as this. “Very well. I’ll ask Marion to bring you out some milk and biscuits later. All right?”

Scottie gave her an approving smile, turned away from the adults and ran back in the direction of the treehouse. Pamela turned to Gabriel and gestured to him to come in.

“Sorry to drop in on you like this,” Gabriel began, wiping his feet thoroughly on the doormat and unbuttoning his coat, which was looking more presentable this morning after some emergency cleaning work. The hall of the house had a feeling of restrained grandeur about it, with its polished wooden floors and broad staircase up one side, which made him feel a bit shabby by comparison. “Please don’t force Scottie to stay out in the cold on my account.”

“It’s quite all right, Father,” said Pamela, cheerfully, leading him into a vast, richly furnished drawing room. “I daresay you haven’t come for a quick cup of tea and an appeal for the roof fund, have you?”

Gabriel found Pamela’s courteously direct approach as disarming as her daughter’s, but he took a seat near the roaring fire whilst Pamela stepped back into the hall to hang up his coat and hat. The room looked as though it had once been two much smaller rooms, which had been knocked through, leaving a central arch where the old wall had been. There was a clear division between the cosy end of the room, in which he was seated, and the far end, where a grand piano stood under a cloth covering and various paintings hung on the walls, separated by mirrors that gave the room an even larger feel. In the bay window, which overlooked the garden, a pleasant little reading corner had been arranged, with two low bookcases and a recently upholstered armchair in the middle, which could be separated from the rest of the room by drawing the curtains across. Gabriel’s gaze was drawn to a photograph in a silver frame, in the centre of the mantelpiece. A young man in a military cap, the male version of Pamela’s face, gazed very seriously at some undefined point in the distance, as though staring at his family across the lost years.

Pamela was at his side. “I’ve asked Marion to bring us some tea. Now,” she said, settling herself into the chair opposite, “how may I help you? I was going to visit Agnes this afternoon if Mother could spare the car.”

“That’s very good of you,” said Gabriel, “but it is my hope that Agnes will not be in there very much longer.”

“I sincerely hope not,” Pamela agreed, “but at least it keeps her away from the police. I got the impression from Mr Smithson that you were trying to work it out yourself?”

Another unavoidably direct question; it wasn’t quite cricket somehow. “Well,” he began, steeling himself. “I should like to get to the bottom of this, and you’re quite right that I have come to talk to you about it.”

“Naturally.”

“I shan’t keep you away from your book for too long, Dr Milton, but I should like to ask you a question or two, if that’s all right?”

Pamela made a passable act of indi

fference, but he could see the muscles tightening in her face and knew she was clenching her teeth. “Not at all, Father, though I do wish you’d call me Pamela. I feel as though I’m back in a lecture hall.”

“Pamela, then. Thank you.”

“Well, I told the police all I can remember from that afternoon, which isn’t very much really. I’m not sure there is much more I can tell you.”

“It is not the afternoon I was thinking about, as a matter of fact,” Gabriel began, suppressing his own unfortunate memory of the last time he had asked Pamela a personal question. “I was thinking of the threat Enid Jennings made to you on the evening of your lecture.”

“Father, she was a nasty old trout who said something idiotic,” answered Pamela icily. “If you are going to insinuate that I had anything to do with her death because she made a threat she could never have carried out, then please consider the matter closed. I had nothing to do with her death.”

“You hated her.”

“That’s a non sequitur,” answered Pamela immediately. “She was a vile old bat, and we despised one another. But you must know by now that everyone despised her. I’m not sorry she’s dead, but nor do I rejoice. Her life meant nothing to me.”

He came out with it. “Pamela, why were you expelled from school?”

“What has that to do with the price of fish?” she exclaimed, but her eyes flashed with anger. Gabriel had noted on their first meeting that Pamela Milton was a woman who did not suffer fools gladly, but he suspected that there was quite a nasty temper lurking behind her calm exterior. “It was rather a long time ago, in case you have failed to notice,” she answered tartly. “It did me no harm anyway. My parents were forced to give me a proper education in a decent establishment after that. One could say it was the making of me.”

Gabriel smiled. “I’m very glad to hear it, Pamela, but that hardly answers my question. Why were you expelled?”

In her lap, Pamela’s hands were shaking with what Gabriel suspected was suppressed rage. She stood up and walked to the door, throwing it open as though to see if Marion had arrived with tea, but no such reprieve had come. She turned back to face him. “I fail to see what this has to do with anything, but for your information I was expelled for, I quote, insulting those with whom I disagreed.”

“Mrs Jennings, I presume?”

“The devil herself. I called her an ignorant old witch. Not without reason, I was thrown out posthaste.”

“Why?”

Pamela looked flabbergasted. “Why do you think? For once, the old bag didn’t have a choice! If she hadn’t come down on me like a ton of bricks, she would never have exercised any authority again!”

“I meant, why did you say that?”

“Probably because she was an ignorant old witch, I suppose.”

“Pamela . . .”

Pamela went very quiet. Her hands no longer shook; they were clenched together so tightly that the slender white bones showed beneath the taut flesh. She was employing every scrap of energy to avoid showing any weakness before Gabriel. “She called me a dirty Jew,” she whispered. “Dirty little Jewess. She used to make me sit alone in the far corner of the classroom in an effort to protect the others. I don’t even know how she knew about it. I have one Jewish grandfather, and he died years ago.”

“I’m sorry,” offered Gabriel gently. “Did you tell your parents what had happened?”

Pamela shook her head. “I didn’t want to. I knew my father—God rest his soul—would have taken it very badly. His family had worked so hard to be accepted here all those years before. When his father arrived as a child, his parents even changed the family name to sound less foreign. Milton sounded so English, the name of one of the greatest English poets of all time. For all I know, she might simply have made an educated guess, but she had a tendency to find ways to hurt people.” Pamela’s eyes had closed with the effort of telling the story. “When I came home and told my parents I’d been expelled, of course they wanted to know why. I couldn’t lie to them, and my father would never have given me a minute’s peace until I had told him the truth.” She paused to draw breath, her eyes still shut, but she sounded as though she had been running. “That was why I didn’t get into trouble at home. My parents would never have accepted behaviour like that for any other reason. My father said I was to learn more sensible ways to express my disgust in future, but other than that, he left me alone.” She glanced up at Gabriel with a sense of palpable relief. “A few weeks later, my trunk was packed, and I was on a train bound for the frozen north. It was a convent school. One of the sisters decided that I would be their first girl to go to Oxford, and Mother Mary Imelda was never wrong.”

Gabriel paused, unwilling to draw the conversation away from Pamela’s story, but the thought jumped out at him like a serpent. “Pamela, to your knowledge, was Mrs Jennings a Nazi sympathiser?”

Pamela shook her head again. “How would I know? We never spoke again, but I wouldn’t put it past her. She was behaving like a Nazi before the Nazis had even come to power. And if she had been, she would have been intelligent enough to keep it to herself.”

“Do you know anything about the bunker?”

Pamela looked at him as though he were an idiot. “Hitler’s bunker? We all know about it. He topped himself down there.”

“Pamela, I think you know what I mean.”

Pamela looked disdainfully in his direction. Any former emotion she had been suppressing had evaporated. “If I knew what you meant, Father, I should not have given you an answer you did not want.”

They were interrupted by the sound of the door opening and the appearance of an agitated young woman armed with a tea tray. Scottie was bringing up the rear. “Awfully sorry, Madam,” said Marion breathlessly, setting down the tray on the table between them. “Did you really mean me to serve Miss Charlotte’s elevenses in the treehouse?”

“It’s quite all right, Marion,” answered Pamela apologetically. She rose to her feet to talk to the woman at eye level. “Charlotte can take her elevenses into the treehouse herself. She can use her thermos to avoid spillages.”

Scottie was quietly sidling her way into the alcove in the bay window. Gabriel knew she was itching to join the conversation. “It’s quite all right, Mummy,” she put in sweetly. “I could just as easily eat in here with you.”

Pamela chuckled. “Away outside! I’ll call you from the window when it’s time to come in.”

Scottie sighed with theatrical hyperbole before stomping noisily out of the room with Marion. Gabriel was reminded of the frustration he had felt as a child, sitting on the landing and peering through the bannisters as his parents and their guests stood with their preprandial drinks, chattering about matters that felt very serious indeed and very important. It was not easy to be an inquisitive child on the fringes of an adult drama. “I shan’t keep you much longer,” said Gabriel as Pamela poured the tea. “I can’t bear keeping you from that poor child any longer. I feel like a usurper.”

Pamela laughed politely, but Scottie’s sudden appearance had thrown her, and she struggled with the task of picking up the delicate milk jug and placing the silver sugar tongs within Gabriel’s reach. The sugar bowl was bulging with neat white lumps, he noticed, and he doubted she had filched her supply entirely from George Smithson’s cupboards. He made no comment as he helped himself.

“She gets far more attention than most children,” Pamela remarked, “and I shan’t be packing her off to boarding school either. I must say that I am thoroughly enjoying the task of educating her myself.”

“She’s a delightful child,” said Gabriel, only partly to ingratiate himself with a woman he was about to risk angering again. “Pamela, if you’ll forgive my asking, is George Smithson Scottie’s father?”

Pamela started, never a good sign, and then burst into a fit of entirely forced laughter. “Dear me, no! He is very fond of her, and he indulges her because he knows it is an easy way to reach me, but no, no, no! I’m afra

id he isn’t. I wasn’t lying when I said that Scottie’s father died during the war. I’m sure he meant to make an honest woman of me when he returned, but fortunately for him, he was spared the horror.”

The quip was in bad taste, but it had the desired effect, and Gabriel did not risk questioning her any further. He finished his tea as quickly as possible and took his leave.

13

How on earth did other detectives deal with their cases? Gabriel mused, as he dashed in the direction of the police station. The fact was that literary sleuths tended to be gentlemen with private means who had all the time in the world in which to indulge their curiosity. They could fight an intellectual battle for justice without having to worry about getting back in time for hearing confessions or training altar boys or comforting the dying. For that matter, how on earth had Father Brown managed it? A fine detective he certainly was, but what sort of a shirker of a priest must he have been? When had he ever had to bother himself with the minutiae of parish life, with the souls of tiresome, whingeing old ladies and fatherless children, and reforming gamblers and wife beaters? Perhaps the world had simply been a more ponderous place before continents had descended once again into the mire of a world war when millions were still bearing the wounds of the last one.

He was getting old and nostalgic, thought Gabriel despondently, further quickening his pace at the unimposing sight of the town constabulary as it emerged into view. It was not a view to strike fear into the heart of seasoned criminals or to evoke a sense of awed reassurance from law-abiding citizens. The police station was nestled into the middle of a long Victorian terrace, the familiar blue light hanging over the fifth door. Years ago, the O had fallen off or been stolen from the sign, making it look as though Gabriel were entering the residence of P LICE Esq.

He was still smiling at the thought as he arrived at the front desk and encountered the most fed-up-looking constable in the history of British policing. “Good morning, Stevens,” greeted Gabriel, with hopeful cheerfulness. “How’s little Marjorie feeling? Getting stronger, I hope?”

The Vanishing Woman

The Vanishing Woman