- Home

- Fiorella De Maria

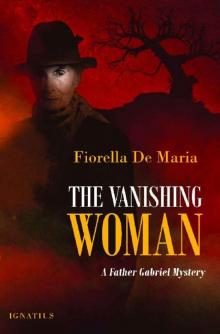

The Vanishing Woman Page 2

The Vanishing Woman Read online

Page 2

Pamela took out a silver fountain pen. “I would so love to see her again, Doctor; it’s been so long. I don’t think I’ve spoken with Therese since before her pregnancy, and the baby must be—what, three or four months now?”

“Eight months. You’ve been away longer than you remember!” He watched Pamela as she wrote a short message for her friend on the title page and signed her name with a flourish. “I say, why don’t you come to dinner one evening next week? I know you’re very busy writing and all that, but the family would love to see you again and, of course, your little one.”

“She’s not so little either, Doctor, growing much faster than I should like. How is Therese? She wasn’t too bright last time she wrote.”

Dr Whitehead sighed, picking up the book and holding it open to ensure he did not smudge Pamela’s writing. “A bit up and down since the birth, I’m afraid. Life’s not made any easier by Freddy being away.”

Pamela nodded sympathetically. “It must be very hard being an army wife. I’m not sure many people realise we’re still fighting wars.”

“Quite. It’s hard for her not to feel a bit depressed with Christmas coming and the poor man far away.”

Pamela smiled. “Don’t worry, I’ll cheer her up. Tell her I’m coming to make a fuss of her.”

At the back of the hall, Gabriel considered that he really ought to buy one of the lady’s books since he had come along to be entertained by her all evening. He was an avid reader of conservative tastes and had always tended to regard a book as worth reading only if its author had been dead at least fifty years, but he thought he could make an exception for Pamela Milton. He searched in his pocket for his wallet and made his way to one of the tables, picking up a copy of her latest novel, That Singular Anomaly, a volume the thickness and weight of a doorstop. Well, the winter evenings were so long, he thought, turning the book over for clues about its contents, but he was distracted by what sounded like a scuffle some way in front of him.

Now that she had come off the platform, Pamela’s slight figure was harder to see, but as he stepped closer to her, Gabriel noticed that she was locked again in an argument with Enid Jennings, who, not satisfied with sabotaging the discussion, had come back to settle the score privately. With the background noise obscuring their conversation, Gabriel could only make out snippets of what was being said and told himself he was not really eavesdropping. They were, after all, talking in public and had to expect to be overheard at least in part.

“Worst pupil I ever had the misfortune . . . ungrateful . . . arrogant . . .”

“Late in the day . . . unqualified . . . laughable . . .”

Gabriel inched closer, nudging past the two or three people who stood between him and the conversation, before realising that he was not the only one observing the two women locking horns. They might have been a tableau of the perennial conflict between generations, particularly generations of women; the older one was bitter, tired, suppressing a lifetime of frustration, anger and envy. She was a woman in a persistent state of attrition against the world. The other was energetic, arrogant, self-assured, still acquainted with enough enthusiasm and confidence to believe that she could carve out a place for herself in the world. The women, thought Gabriel, had quite a bit in common with one another. Both were strong-minded, intelligent, independent and tenacious, but the division of not just years, but years of cataclysmic change had caused the two to be pitted against one another as no two generations had ever been before. Or perhaps it just seemed that way. Perhaps every generation believed the older or the younger did not understand their own struggles and had nothing to say to them.

“I am giving you a friendly warning, my girl,” said Enid Jennings, looking every bit like Lady Catherine de Bourgh without the class or gravitas. “I destroyed your silly little life once, and I can do it again. Think very carefully before you defame me.”

Pamela returned her contemptuous glance with an even stronger one of her own. “Don’t threaten me, you old witch. I know exactly the sort of person you are. You have a lot more of a reputation to lose than I have.”

Enid Jennings lost her temper, a few seconds, thought Gabriel, before Pamela would have done, her face flushing with rage. “Stop it!” she shrieked, far too high pitched to command any respect. “You’re irrational, you always have been!” She turned her back and began walking away to make absolutely sure that Pamela could not respond, saying over her shoulder as she went, “You have been most offensive, Pamela. I really am most offended.”

George Smithson was at Pamela’s side with the tea, a rather pathetic token of appreciation under the circumstances. “Do you need a little time outside?” he asked, gesturing towards the door. “Why not have a breath of fresh air and then we can start tidying up the books?”

Pamela nodded. “Thank you, George. I’m sorry. I do hope it hasn’t spoiled the evening. I’ll go outside and have a cigarette. I won’t be a moment.”

Gabriel glanced at George as Pamela walked away, noting that Pamela’s was not the only angry face in the room. “Would you like me to check she’s all right?” asked Gabriel, trying not to flinch as George began loading books into boxes with rather more violence than was necessary.

“Please do, Father,” he said, in the tone of a man trying desperately to keep his cool. “I shouldn’t say this, but I don’t like old ladies very much. If a young man had behaved like that, he would have got a black eye from me.”

“You have my sympathies. Not that I suppose I should say that.”

Gabriel knew Enid Jennings, though she had not once entered his church during the months he had worked there. He knew her by reputation as a cantankerous busybody, but not in the conventional small-town sense of being the local gossip, always whispering in corners, always stirring up arguments in her desire to make the world a better place by interfering in it at every possible opportunity. No, Enid Jennings had her own brand of destructive behaviour, which made her the bane of any organising committee. Her appearance inevitably signalled the end of a happy occasion as she would go out of her way to start an argument with somebody, take issue with something or explain very loudly how very much better she could have done things, but no one cared about her enough to ask. He was almost relieved that Enid had made such a swift exit when faced with a level of opposition she had not anticipated, as it saved Gabriel from the unpleasant obligation to remonstrate with her, even though he knew it would never make any difference. Instead, he followed Pamela out to see if she required assistance.

By the time Gabriel had left the hall and the anteroom for the stone steps outside, Pamela was inhaling very elegantly from a cigarette neatly wedged into a tortoiseshell holder. She glanced up at him with a somewhat rueful look. “I hope you haven’t come to give me a telling off, Father,” she said, leaning back against the brick wall of the building. “She could have had the decency to stay away, couldn’t she? Vile woman.”

“I’m not sure it was wise to be quite so rude to her,” suggested Gabriel, feeling as though he were walking on tiptoe across a minefield. “She’s a good deal older than you.”

“What the devil has that to do with it?” demanded Pamela, looking askance at him. “Where does the social convention come from that says an old person does not have to be as polite and considerate to others as everybody else? She was rude to me, she did everything possible to ruin the evening, and you suggest to me that I should not have been rude?”

“I said I was not sure it was wise,” corrected Gabriel. “I gather she is not a pleasant woman to cross, not that I have never had the pleasure myself.”

“If I were you, Father,” answered Pamela, “I would stay well away from her. She brings nothing but misery and discord wherever she goes. Just because she terrorised the children of the town for years in what she laughably called a school, she imagines the world and his wife owe her a living. Please shoot me if I ever get like that.”

“I most certainly will not,” replied Gabriel, returning

her exasperated smile with one of his own. “Much has changed in the world, but fortunately murder is still universally frowned upon.” He paused, allowing her time to take another drag on her cigarette before continuing. “Would it be impertinent of me to ask what she meant when she talked about destroying your little life?”

Pamela winced violently, and Gabriel knew he had made a mistake before she responded. “I’m sorry, Father, but you had absolutely no business eavesdropping. You’ve got quite a nerve asking me to explain something you were never intended to hear.”

“Forgive me, I’m just a little concerned for you. She appeared to be threatening you, and if she’s making trouble, I was simply going to suggest—”

“Father, I am quite capable of looking after myself,” interrupted Pamela sharply. “I always have done and I always will. I don’t need men of any shape or form to protect me. Thanks all the same.” She stubbed out the cigarette with a deft movement and returned inside to help put the hall to rights.

Gabriel watched her firm, determined tread as she moved away from him, and not for the first time in his life, he wished he had kept his mouth shut.

2

Gabriel arrived back at the presbytery to find Fr Foley dozing in his armchair by the embers of a dying fire. The old man’s collapse with a heart attack had been the main reason Gabriel had been sent away from St Mary’s Abbey to assist in the running of this parish, and it pleased him to see that Fr Foley had started to show signs of recovery. That said, the healing process after such a shock was lengthy, and the old man still struggled with tiredness. He seldom ventured out of an evening if he could avoid it, and in spite of the hour-long nap he took every afternoon immediately after lunch, he invariably fell fast asleep by eight o’clock or felt too dozy to be of any earthly use to anyone.

As soon as Gabriel had changed out of his wet shoes into comfortable slippers, he turned off the wireless Fr Foley had left on and stoked the fire to get it going again so that he would have some warmth as he ate his supper. When a few pathetic flames had been coaxed into life, he pottered into the kitchen, where half a pork pie had been left for him on a plate, accompanied by two pickled gherkins, some slices of tired-looking bread and a glass of cider that made up for everything else. Cider always reminded Gabriel of the abbey and the community he had not seen for so many weeks. He should not complain about the pork pie really, he told himself by way of distraction, even if he had to share the thing with another person. There had been a time when he had almost forgotten what it was like to see quite that much meat on one plate, however processed and adulterated it was, and he took it through to the sitting room so that he could eat more comfortably.

Fr Foley stirred at the sound of movement in the room, opened his eyes and looked bewilderedly at his friend. “Your spectacles are on the table beside you,” said Gabriel gently, “before you mistake me for a burglar.”

Fr Foley chuckled, reaching out to pick up his glasses and put them on. “You’d be the town’s cheekiest burglar if you broke in, helped yourself to a meal and sat by the fire to eat it,” he commented, attempting to sit a little more upright. “Did you have a pleasant evening?”

“Very interesting talk,” Gabriel responded. “I suppose you know Pamela Milton?”

“Rather!” he said. “Ever such a naughty little thing, as I recall. Always in trouble with someone or other, very rarely with me, though. I’m sure she was most entertaining.”

“There was quite a rumpus actually. Mrs Jennings turned up and started a row. I’m afraid it all became pretty unpleasant. Pamela was furious.”

Fr Foley sighed. “Dear, oh dear, that woman is quite a menace. I’ve known plenty of those types over the years, tut-tutting about the length of a young girl’s skirt or the shade of her lipstick and not noticing that they’re consumed by pride themselves. Did you buy a book?”

“Yes, I’m sorry, but I rather felt I ought. It cannot be a very easy life, supporting oneself as a writer, and I don’t suppose she earns a great deal at the university. It looks as though it might be a rather good read. She was certainly interesting enough to listen to.”

Fr Foley peered at the cover. “That Singular Anomaly. Now where have I heard that before?”

“Gilbert and Sullivan, Father; it’s from The Mikado. I suppose it’s intended as a self-deprecating joke: that singular anomaly, the lady novelist.”

“Well, she’s certainly that, and not just because she scribbles for a living.” Fr Foley’s eyes closed with the effort of making cheerful conversation. “It’s no use. I had better get to bed before I fall asleep again. Can’t have you carrying me up the stairs, can we now?”

Gabriel set down his food and helped Fr Foley out of his chair, watching anxiously as he trotted through the room and up the stairs. He could not pretend he did not miss the abbey terribly on an evening such as this, and he was grateful to have at least some company to come home to when he was so unused to being alone. He reached over and switched on the wireless again to avoid sitting in silence and listened to the BBC Home Service as he finished his food. After he had locked up and taken a quick look at the following day’s schedule, he thought it prudent to retire early and went to bed.

Gabriel was to pass a troubled night. The heavy rains that had so recently brought floods to a town inconveniently situated in a valley returned to haunt his hours of rest. It struck him as he lay in bed, listening to the hammering of raindrops against the skylight over the landing, that the rain was not quite as heavy as it sounded, magnified like that against the glass, but the recent memory of that terrible week disconcerted him. Farmland had been covered in three feet of water, autumn crops had been ruined and a young man had purportedly drowned trying to cut across the quagmire in the dark after a drunken night out with friends. All in all, it has been a ghastly time for a population that had already suffered a great deal over the past years. Being a garrison town, the area had been host to many regiments during the war years. They were stationed there just long enough for the soldiers to fall in love with the local girls before being posted to far-flung parts of the world, never to return.

Gabriel gave up trying to sleep and sat up sulkily, resenting his mind for refusing to switch off when he was in desperate need of rest. He pulled on his dressing gown and slippers and crept softly downstairs to avoid waking Fr Foley, whose room was just across the narrow landing. Long before he entered the abbey, Gabriel had established a rule that if he could not sleep for more than twenty minutes, he would get up and do something useful to make himself relax—have a hot drink or finish the crossword, some small task that would allow his mind to unwind. He had suffered insomnia much more rarely at the abbey, but then life was so much more regimented there, so much more predictable. He missed the very discipline of monastic life that he had struggled to obey before Abbot Ambrose had packed him off here, partly because Fr Foley needed some help and partly perhaps for his own sake, to test whether he was suited to the monastic life at all.

As Gabriel sat in the kitchen, sipping his cocoa, he thought about Enid Jennings and the scene she had caused. It rankled him that he had been relieved by her sudden exit because it had prevented him from doing the decent thing and suggesting she apologise, but the whole conversation troubled him all the more because Pamela had quite reasonably refused to discuss it with him. There had been absolutely no reason why she should have taken him into her confidence. He had demanded an explanation about words he should never have heard. Yet he had heard them, and the more he thought over that confrontation, the more his misgivings grew. He knew that people made veiled threats to one another all the time, and, as usual, he was probably making a fuss about nothing, allowing an unexpected outburst to keep him from sleep. Nevertheless, the nagging sense that something was wrong or about to become very wrong persisted.

He would visit Mrs Jennings in the morning, Gabriel told himself as he washed up the cup and saucer. For his own peace of mind, that was all. He convinced himself, as he went back ups

tairs to bed, that when approached on her own, Mrs Jennings might be quite amenable. Like Pamela, he suspected, she might be the sort of person who puts on a mask in public to hide a gentler, more vulnerable side. He had to battle quite hard as he dozed off to reassure himself that this was the case. After all, it was quite possible that Enid Jennings was simply a deeply nasty individual bent on upsetting everybody, who would sooner hurl a scathing reprimand at him than listen to a word he said when he appeared at her door in the morning.

It would help, thought Gabriel, if he had some harmless pretext to see her, if perhaps she had left her spectacles or her purse behind, but she had clearly left with everything that belonged to her—she was not the sort of person who could be accused of being scatterbrained. Of course, he wasn’t to know that. In fact, he might have picked up some item or other that someone else had dropped. He might quite innocently think it were hers and be trying to be a helpful citizen by dropping round and giving it back. Fr Foley never needed his reading glasses after Mass; he always left them in the sacristy before he took his short, gentle stroll to the shops. It would hardly be stealing if he took them back again as soon as he could.

The whole idea felt a little more shabby next morning when Fr Foley greeted Gabriel cheerfully as they passed one another in the doorway of the sacristy and Gabriel found the reading glasses sitting obediently in their usual place on the windowsill. He took a deep breath, cursed his moral cowardice for needing such a ludicrous ruse to avoid confronting an old lady and put the glasses in his pocket.

The Vanishing Woman

The Vanishing Woman