- Home

- Fiorella De Maria

The Vanishing Woman Page 4

The Vanishing Woman Read online

Page 4

He had scarcely gone ten paces when a hand grabbed his ankle, throwing him into a state of panic. Douglas wrenched himself free and gave his assailant a sharp kick; he felt the toe of his shoe strike the soft tissue of a human face before he staggered back, resisting the urge to make a run for it. “Who’s there?” he shouted, shining the torch in the direction of the now hunched figure before him. He could feel tiny splinters prickling the palm of his hand as he clenched his weapon. “Get up!”

That was when he saw her. Curled up in the foetal position, shivering and struggling for breath, lay Agnes. Douglas dropped to his knees immediately, pulling her hands away from her face. He could feel the sticky wetness on her fingers and knew from the bitter, metallic smell that it was blood. “Help me!” she sobbed. “Oh please, I’m so cold!”

Douglas battled to pull Agnes to her feet, holding her by the wrists to avoid having to touch the blood again; his stomach was in knots as it was. “My God, Agnes, what have you done?”

It had undoubtedly been a mistake to call the police, thought Douglas, but under the circumstances he had not been able to think of a more appropriate course of action. He had relaxed a little once Agnes had washed her hands and collected herself sufficiently to accept a glass of brandy. It turned out that the blood on Agnes’ hands was, in fact, hers, emanating from her nose, thanks to the kick from Douglas as he had attempted to escape his invisible aggressor. Douglas suspected almost immediately that the two of them had—separately, it appeared—been victims of their own imaginations. He had convinced himself that there was danger in the woods because Agnes had wandered out of the house and made it look deserted; it was dark and cold, and he was probably rather drunk. Even his momentary belief that Agnes had killed someone looked absurd when he gave it a moment’s thought. On Agnes’ part, she had convinced herself that she had seen her mother walking along the path and then apparently vanishing into thin air. Since their mother had not returned home as planned and it was most unlike her to be late, however, Douglas had taken the precaution of informing the police.

The constable who came belligerently to the door took a statement from Agnes and a rather shorter statement from Douglas before letting forth a sigh as though to leave neither of them in any doubt that he would rather be doing anything else on a Saturday evening than talking to them. The situation was rendered worse by the fact that Agnes had a dreamy way of talking when she was distressed that made it seem as though she were slipping in and out of a trance, which hardly helped the case for her sanity.

“Let me see if I’ve got this straight,” said the constable, poring over the notes he had made in his book. “Miss Jennings was not the victim of an assault because the bloody nose she received from you, Mr Jennings, was the result of an accidental blow to her face dealt because you believed her to be in the process of attacking you.”

“It wasn’t a blow, it was a kick,” Douglas interrupted, “and it wasn’t even a deliberate kick, come to that. I was trying to shake her off and my shoe collided with her face.”

“Indeed,” answered the constable dryly. “Could happen to anyone. Now, Miss Jennings, you say that you were looking out of the kitchen window not long after four o’clock when you saw your mother walking up the path. You were distracted for a moment by the kettle whistling, and when you returned to the window she had disappeared. She never came to the house.”

“I know how mad it sounds,” said Agnes, who honestly could not have looked madder under the circumstances if she had tried. Her face was pale and pinched with anxiety, her eyes were red from weeping and her clothes were damp and dirty from her lying outside on the ground. Douglas wished he had urged her a little more strongly to get changed before the police arrived, but even if she had bathed, dressed in her finest and kept her composure throughout the entire interview, her nose—bruised and swollen, still bearing traces of dried blood—made her look like a crazed Dickensian match girl. Her appearance might elicit sympathy, but she hardly had the makings of a credible witness.

“Might I ask what you were doing on the ground in the first place?” enquired the policeman. “Did you lose your footing in the darkness perhaps?”

Agnes did not appear to notice that he was suggesting an innocuous explanation to her. “I’m afraid I’m not sure how I got down there. I think I must have blacked-out or something. I’m afraid I do that sometimes.”

“Really?”

“Look here, constable,” Douglas broke in, “my sister is not in the best of health. She is rather prone to fainting and dizzy spells.”

“Indeed?” He looked back at Agnes. “Might you perhaps have taken a funny turn at the window then?”

“Yes,” said Douglas before Agnes could find her voice. “That might well have happened, now that I think about it. What do you say, Aggie?”

Agnes ignored her brother’s steely glance in her direction. “I’m sure that didn’t happen.”

“But how could you be sure?” The constable noticed Agnes opening her mouth to challenge him and continued. “We may have to assume that you were mistaken when you looked out of the window, Miss Jennings. It was getting dark, you were expecting her back at about that time so you imagined that you saw her. An easy enough mistake to make.”

“How is it an easy mistake to make?” Agnes demanded, suddenly coming to life. “How likely is it that I accidentally saw my mother walking towards me? I’m certain I saw her.” She looked at Douglas for support, but he stared fixedly at the hearth rug. “Well, surely you believe me? Why would I make up a story like this?”

Douglas turned to the constable, whom he had met on a number of occasions going about his lawful business; he decided it was time to steer the conversation in a more reasonable direction. “PC Davenport, I realise this all sounds rather incredible to you, but one thing we are certain about is that our mother is missing. We expected her back hours ago—even four o’clock was a little late for her—but we are very concerned that she has not returned by now. Whatever has happened, she is not where she ought to be.”

Davenport relaxed almost imperceptibly. “Isn’t it possible that she might have decided to stay at her sister’s another night perhaps? They may have been enjoying a jolly day out and lost track of the time. Before they knew it, she had missed the last train and decided to wait until the morning to return home. She’s a grown woman; she’s at liberty to make a last-minute change of plan.”

“It would be very out of character for our mother to do that,” Douglas stressed. “She was not really the sort of person who made last-minute changes of plan.” He could not honestly imagine his mother having a jolly day out either, for that matter, but that was hardly worth sharing.

“Have you telephoned your aunt to ask if she is still there?”

Douglas raised his eyes to heaven. “She has no telephone, or of course we would have checked before troubling you. Look, if she did arrive back in the town, people will have seen her. The stationmaster could tell you whether she got off the train at this station. It can hardly be beyond the wit of man to go to my aunt’s house and check in person if she is still there?”

“Well—”

“If the police are too busy with the small matter of my mother’s disappearance, I can go and check tomorrow.”

“Yes, thank you, Mr Jennings,” Davenport responded, getting up to leave. “There are certainly a few enquiries we can make; don’t trouble yourself about that. If it’s not too impertinent, I would suggest it might have been better to call a doctor than a policeman.”

Douglas propelled Davenport in the direction of the sitting-room door. “Get out!” he snapped. “There is absolutely nothing wrong with my sister’s mind. If she says she saw our mother walking towards the house, she saw her. Now you had better make sense of this little puzzle, constable. A woman is missing, and her life may well be in danger.”

When Douglas had seen PC Davenport out, he locked the door with a little more care than usual, making sure the key clicked twice as it

turned in the lock, then pushing across the two stiff, heavy bolts as an added precaution. It was pointless, he thought, as he gave the door a last rattle. A burglar could quite easily smash a window, and they were far too isolated for anyone else to notice, but he felt the need to fortify his castle. He could hear Agnes sobbing in the sitting room and groaned. Since the war, Douglas had felt a constant sense of his own helplessness, and he did not believe that he would ever shake it off. He stepped closer to the sitting room, watching as Agnes curled up on the sofa, her face buried in her lap, her arms wrapped around her knees. He was overwhelmed by a wave of nausea. “Aggie, stop it!” he hissed, but she did not acknowledge him. “Please don’t, nobody’s hurting you. You—you can’t stand her! Nobody can!”

When Agnes continued to ignore him, lost in her own grief or confusion, Douglas turned on his heel, slammed the sitting-room door shut and stormed upstairs to his room. I’m turning into my mother, he thought bitterly, throwing himself onto his bed. Hiding fear behind rage like the louse I am. It was so much easier to be angry.

4

Monday morning dawned crisp and cool but without bringing the heavy snow for which the children had been desperately waiting. Gabriel stopped at the bookshop on his way to buy the morning paper, keen to discover whether George Smithson had received the copy of Newman’s Apologia he had ordered weeks ago. The bookshop was a favourite haunt of Gabriel’s; it reminded him in some ways of the monastic library, with its seemingly endless bookshelves heaving with knowledge and plenty of little cubbyholes in which to sit and leaf through a volume or two before buying anything. It was not as peaceful and quiet as a library, with the bell over the front door jangling every time a customer came in so that George would know to come into the shop if he were in the back room making himself a cup of tea. George was kept mercifully busy, but even if people talked, Gabriel noticed that customers in bookshops tended to whisper as they would in a library, almost as though they feared to disrupt the serious atmosphere of the place.

The shop was relatively quiet on a Monday morning, but Gabriel saw that George had company. A little girl in a gingham dress and a thick red cardigan sat on the counter, swinging her legs as she chatted easily with George. Gabriel guessed that she was about nine years old and noted the resemblance immediately; she looked exactly as he imagined Pamela must have looked once; long dark plaits hanging forward over her shoulders, a lovely Madonna face, so perfect it could have been painted, and a knowing smile she had also inherited from her mother. He stood on the doormat, not wishing to intrude upon the conversation, but they stopped talking immediately and glanced in his direction. Only when they were silent did Gabriel register that they had been speaking in French.

“I am most impressed,” said Gabriel to the child, as he approached the counter. “Your French is excellent.”

The child jumped down from the counter, turned and picked up the copy of The Wind in the Willows she had been leafing through—it had evidently been their chosen topic of conversation—before giving Gabriel her full attention. “Not as excellent as Mummy would like,” she said with a mischievous giggle. “Mr Smithson is helping me with my accent.”

Gabriel held out a hand to her. “You must be Charlotte,” he said. He expected her to shake his hand, but to his surprise, she kissed it instead, an act of piety he had not quite anticipated from the daughter of the town’s mischief maker. He chided himself for making an unfair judgement. “Are you here for the holidays? The schools haven’t broken up for Christmas yet.”

“I learn at home,” explained Charlotte. “Mummy says schools are just bastions of conformity.”

Gabriel struggled to suppress his laughter; there was something very endearing about listening to a child enunciating concepts she did not understand and could only just pronounce. “I see.”

“I tell you what, Scottie,” said George, “why don’t you go into the kitchen and get yourself something to drink? Your mother left your milk in the fridge for you. You know where the glasses are.”

Charlotte gave him a sidelong look that made it quite clear she knew she was being got out of the way, but she trotted out of sight happily enough as if to say, “You good people are too boring for me anyway.”

“Why do you call her that?” asked Gabriel, as soon as the child was out of earshot. “No Scottish blood there, is there?”

George smiled before disappearing behind the counter. “Her nickname started out as Chottie. If you think about it, there aren’t many shortenings of Charlotte, either Charlie or Lottie, and Pamela didn’t really like those very much.” He reemerged, heaving onto the counter a large box, which he began cutting open. “So she was Chottie until a couple of years ago, when she was given a tartan beret as a birthday present, which she refused to take off for about six months, according to Pamela. You know the way small children get attached to things sometimes? The first time I saw her dressed like that, I said, ‘You’re not Chottie, you’re Scottie,’ and somehow it just stuck. She has outgrown the beret, or it was lost or became too ragged to wear anymore, but she can’t seem to lose the name. Now—” George began taking out and unwrapping his latest haul of books. “These arrived first thing this morning, thank goodness. Can’t have Mr Pitman coming in yet again wondering if his copy of Aristophanes’ The Birds has arrived.”

“Perish the thought. Any sign of my—”

“Aha! Here we are.” George pulled out Newman’s Apologia with the panache of a magician pulling a rabbit out of a hat. “Yours, I believe?”

Gabriel was busy inspecting the bindings as George opened his sales book and wrote down the details when the bell chimed with unexpected violence, causing them both to stop what they were doing and look in the direction of the noise. Douglas Jennings was standing on the doormat, the door left gaping open. “Thank God you’re here, Father!” he exclaimed without further introduction. “Fr Foley said he thought you’d come this way.”

“For goodness’ sake, come in and close the door!” insisted George. “You’ll freeze us all to death.”

“Sorry,” murmured Douglas, pushing the door shut in what was almost embarrassment. “I’m so sorry, Father, but I couldn’t think of anyone else to ask. Mother’s gone missing; she did not return home as expected after her visit to her sister’s. The police are being absolutely ghastly about it, and poor Agnes is beside herself. She keeps saying she saw Mother approaching the house. The police are treating her like a lunatic, and I’m beginning to think they have a point. I know this isn’t really a spiritual matter but—”

“Of course, I’ll go and see her,” said Gabriel simply, putting Douglas out of his misery. “Is she at home?”

“Yes, I don’t really like to leave her alone for very long in the state she’s in, but I had to find you. I’ve already been to the school to ask Mrs Howse to take Aggie’s class for her, and I really should be at work myself. I’m terribly late as it is, and Mr Pitman is such a stickler for punctuality. I shall be up half the night catching up with everything I’m missing this morning.”

“I suspect Mr Pitman might make an exception to the rule under the circumstances.”

“I hardly think so; we have to be in court tomorrow.”

Gabriel turned to George as they opened the door to leave. “I wonder if you could ask Charlotte—Scottie—to run down the road to the presbytery and tell Fr Foley I have been called out on an urgent matter? Would that be all right?”

“I don’t mind at all, Father,” came a bright voice from the door to the back of the shop. Charlotte had evidently overheard every single word of the conversation and wanted them to know it. “You have been called out on an urgent matter. Is that right?”

“Yes.” As Gabriel and Douglas left the shop, Gabriel realised he had forgotten about his book. He opened the door again. “I’ll return for the book later,” he told George before following Douglas out into the street. “I hope it was all right sending that little one off on an errand. She can’t be more than about nine, I suppose

, but she’s so articulate, one almost forgets.”

“Oh, she’ll be quite all right,” agreed Douglas. “It will take only five minutes, and she’ll enjoy the walk. But bear in mind, Scottie’s only seven. She’s quite tall for her age, and she’s growing up surrounded by adults. That’s why she seems so much older. Anyway—”

“Yes, I’m sorry. Fill me in on the details as we go.”

“Well, it’s better if you hear it from Agnes, of course,” Douglas began, “but what I can tell you is that Mother definitely arrived in town on Saturday afternoon, as she had planned. When we first reported her missing, the constable was inclined to think she had decided to stay at her sister’s a little longer and been unable to get word to us. Frankly, they were not very interested. It hardly helped that Agnes was making no earthly sense, and the constable left making half-hearted promises that he would make a few enquiries. But then, when Mother failed to return home the following day, I travelled to my aunt’s house myself, and she told me categorically that my mother had left at her usual time. After some pestering, the police were prevailed upon to take the situation seriously, and they found out from the stationmaster that Mother had been seen getting off the train and leaving the station.”

“Where were you that afternoon, if I may ask?” enquired Gabriel.

“I had an early lunch at home—Pamela and Scottie joined us, but I left shortly afterwards to have a drink at The Old Bell with a friend. A dozen people will vouch that I was in that pub, not that I suspect it will come to that. I hope I don’t sound unsociable, Father, but I felt rather outnumbered at the lunch table with three females talking at me. You know the way it is.”

Gabriel smiled. “I can well imagine. Was Agnes alone around the time your mother was expected back?”

“Yes.” Douglas frowned over his shoulder in the direction of Gabriel’s limping figure. “You know something, Father, you really ought to take more exercise! Look at you huffing and puffing, and we’re going downhill. I shall have to drag you back up the hill on a hurdle at this rate.”

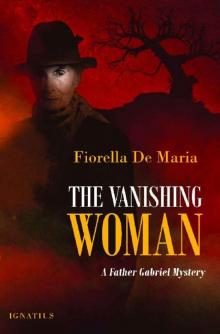

The Vanishing Woman

The Vanishing Woman